Amidst the crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic, people continue to serve their needs and find solace in various forms of activity from their homes, often in solitude, as we socially distance. Many have turned to art and cultural experiences to seek peace, inspiration, and ways of working through their emotions and larger philosophical questions. The next theme I will explore in the CRAG blog is the meditative aspects of art. I will investigate historical and contemporary examples of art made or experienced as forms of meditation from both spiritual and secular perspectives. By exploring a range of geographical locations and time periods I hope to draw upon a wider cultural perspective of mindful looking and art experience that may inspire you to go on a journey of your own into the realm of awe, meditation, and introspection.

Zen Buddhism was the most widely known form of Buddhism in Japan between the 14th and 16th centuries. It originated in India, was formalized in China – where it is known as Chan Buddhism – and from there it was transmitted to Japan. Immigrant Chinese prelates introduced not only the religion, but also Chinese literature, ink painting, calligraphy, and philosophy to their disciples. This resulted in Japanese Buddhists travelling to China for further training, thus entwining spiritual and artistic practices.

Monochrome painting is the practice most closely associated with Zen Buddhism and was originally practiced by monks. Paintings were the result of long periods of contemplation and meditation followed by quick action that would result in an expressive work of art evocative of the maker’s spiritual state and beliefs.

The enso (circle) is a sacred symbol in Zen Buddhism, and one of the most common yet difficult to master subjects of Japanese calligraphy. The enso can mean many things: the beginning and end of all things; the circle of life and the connectedness of existence; emptiness or fullness, presence or absence. When one looks upon an enso it becomes apparent that form and void are interdependent upon one another: “Void is form and form is void.” The philosophical tradition of western existentialism defines nothingness as an emptiness, where nothingness is placed in opposition to being. In eastern philosophies, such as Buddhism and Sufism,“no thing” represents positive aspects such as infinite possibility and necessary balance.

The enso can be closed or open. When it is closed all things may be contained within or excluded from its boundaries; it can symbolize infinity, the no-thing, the perfect meditative state, or enlightenment. When open, the enso represents the acceptance of imperfection as perfect; a connectedness to things that are greater than it; it can be the open circle in which the self flows in and out while remaining centered. There are so many ways to interpret the symbol and it becomes the viewer’s responsibility to make their own meaning and reflect upon their own self throughout the process of mean-making.

Consider spending a few minutes of focused reflection, breathing and looking upon the enso. Notice your thoughts as they pass by, as if you are a passenger on a train platform watching the cars pass by and disappear into the distance. What surfaces? Take note and let it go. Close your eyes for a minute, reopen them and continue looking at the shape. Focus on the sound of your own breath.

Zen Buddhist paintings can be highly symbolic in nature and poignantly express Zen Koans and parables. Zen Koans are philosophical riddles that can be pondered upon for years; parables are moralizing stories that teach a valuable lesson. The Gibbons Reaching for the Moon by Ito Jakuchu represents one such parable. The monkeys link together and strive to reach the reflection of the moon in a pond below. Their reaching is the futile struggle for unattainable happiness. Both unable to relinquish the imagined safety of the bough and unable to reach the moon, they are suspended indefinitely: “So we too find it hard to stop seeking the pleasure we mistake for happiness.” This work of art is both a creation stemming from meditative practice and reflection, and an image to be reflected upon. Imagine how quickly or slowly the painting may have been created by studying the movement of the brushstrokes. Consider the economy of form and abundance of meaning created through the few but very expressive marks that make up this painting.

The many meanings and lessons that can be taken from these painted works rests with the viewer as they meditate upon its relevance to their own life and philosophy. The works are imbibed with the learning and spirit of their masters and carries that aura from the experience of the creator to that of the viewer. The powerful simplicity of enso and Zen parable paintings has endured over long periods of time and continues to offer sources of inspiration and insight.

Now we move to the Han Dynasty (2nd Century BCE) in China to discuss Chinese incense burners as essential aesthetic and ritual elements in the Chinese scholar’s study.

The King of Zongshan brazier is considered one of the finest specimens of Han period incense burners ever excavated. The look and function of the censor played an essential role in the accoutrements of the scholar’s study as they sat considering the cosmos in a deep state of meditation. This particular type of incense burner is referred to as a boshanlu (po-shan-lu), which means magic mountains. They are aptly named for the shape of their lid, a mountainous peak jutting out of waves, alluding to an island mountain in the sea. The torrid mountains and waves represent the dwelling place of the gods, specifically the Three Isles of the Blessed where the legendary Chinese immortals, hermits of perennial youth, lived. Both the elusive mountain islands and the immortals dissolved into mist when approached by humans. When the incense was lit, smoke would waft and curl out from the craggy rock shapes, obscuring mystical animals nestled in its perforations, thus creating a transportative experience.

The Daoist utopia as presented in these objects was not a gentle idyllic landscape, but one with formidably undulating slopes where an incongruous assortment of tigers, hydras, mountain goats, deer, birds, monkeys, and men are engaged in a never-ending chase or hunting scene. It has been suggested that this relentless zoomorphic pursuit was intended to be a visual metaphor for the perpetual force which motivates the cosmos. Sea monsters represented the ocean; tigers, the mountain. Climbing men who may be Immortals or virile elders appear occasionally.

The contemplative aspects of the boshanlu come from the shape that mirrors a mystical realm in Daoist philosophy, as well as the effects created when the brazier is functioning. The curling smoke emulates from the mystic islands in the sea, obscuring and revealing the topography of the objects and the animal and human elements nestled within its fissures. This essential object would have facilitated meditative experiences for scholars as they ruminate upon the vastness of the cosmos.

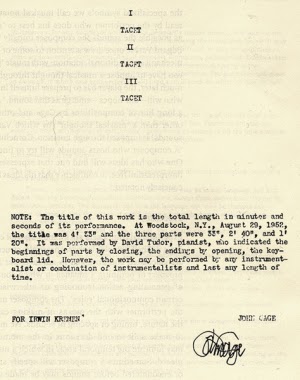

John Cage was an American composer born in 1912. His masterful and highly influential piano composition 4’33 was famously performed by David Tudor in Woodstock, NY in 1952. It is a rumination on the core concepts of silence and chance operations. Over the period of his career John Cage was influenced by Zen, as well as texts like the Yi Jing. Silence was described by Cage as: “not the absence of sound but was the unintended operation of my nervous system and the circulation of my blood.” As I discussed above, the concept of nothing is full of potential in Eastern philosophical traditions. In the performance of 4’33, just as in Cage’s definition of silence, there is an inherent, bodily presence that surges to its own rhythms, creating chance sound arrangements.

David Tudor enters the stage of the Maverick Hall. He sits down at the piano and prepares to perform. He places a stop watch and sheet music in front of himself. Opening the cover of the piano, he places his hands in his lap. There he sits for a total of four minutes and thirty-three seconds, closing and reopening the cover to signal the beginning and end of three sections of the composition. He does not touch the keys, nor does any sound issue from the piano.

When this piece was first performed there was outrage from the artistic community over the absence of sound in what was supposed to be a musical composition. But, there wasn’t an absence of sound. The breath of the audience, the rustling of their bodies, a cough here or there, perhaps a delicate whirring of a fan; all sounds that occurred produced a completely unique atmospheric piece of art that could never be repeated in its exactitude. It recalls the effect caused when one focuses on the sounds around them as they practice total presence during mediation. This remains one of John Cage’s most influential pieces. It hinges on the concepts of chance and silence. Each performed interpretation is completely unique and subject to multiple elements of chance resulting from the sounds experienced during the performance. The nature of the piece is ephemeral and requires interpretation, physical and mental presence to be brought into existence. One may perform the score by freely interpreting its meaning anyway they see fit, leaving it open to near infinite possibilities.

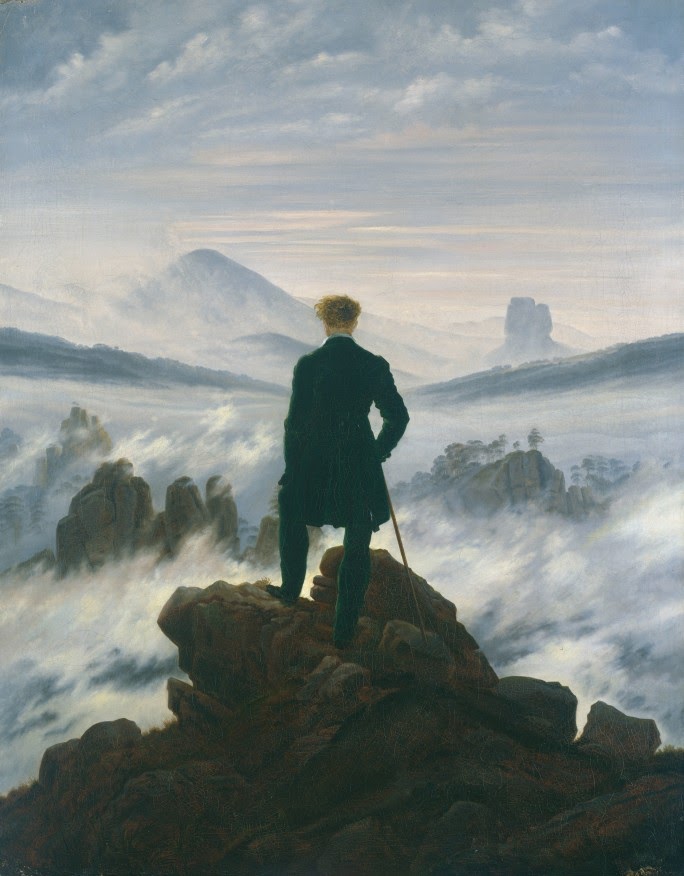

The harmony and solace created by artworks that invoke a sense of awe and wonder in nature resound with the human spirit in a similar way as those motivated by the deeply studied features of spiritual pursuit and insight. Whether works of art originate from the Romantic or contemporary periods there is a history of a love of nature that seeks to understand and convey its awesome power and complexity, and relate the human position to its place within the greater scheme of being.

The paintings of Caspar David Frederich are meant to inspire awe in the sublimity of nature. You look upon an often lone figure with their back to the viewer, absorbed by a natural landscape that invokes a sense of wonder. Friedrich famously once said “The artist should not only paint what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him.” In the presence of natural wonders humans feel small, but also connected to a greater whole, and the majesty of the natural world. It is easy to imagine yourself in the scene because you cannot see the face of the painted human subject. Therefore they become a stand-in for you, as you are transported into the scene and into the sublime. Similar to the other artworks discussed, we are left to create our own meaning and are drawn into a meditative state by the consideration of natural and mystical systems that expound upon the massiveness and complex nature of the cosmos and the world around us. Caspar David Frederich was a Romantic painter who often used nature as an allegorical subject to invoke deeper moral and spiritual meaning.

Studio Drift is a group of contemporary artists from the Netherlands. They create kinetic sculpture, and have been commissioned to design installations all over the world. Much like the paintings of Caspar David Frederich, their work inspires awe in nature, but does so through technology. Shylight is a kinetic installation of light and movement that evokes the grace and energy of flowers as they close at night to conserve resources and defend themselves. The sculpture is inspired by the natural and highly evolved process flowers undertake when opening and closing during what is called nyctinasty.

Having seen an exhibition of their work at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, I can easily say it was one of the most magical and awe inspiring art going experiences of my life. Being in the presence of these wonders of technology that seem to have their own life force caused me to meditate upon the complexity of nature, its poetics and rhythms, and my place, however small, within that wondrously complex system. I would highly encourage you to watch the video of the artwork itself in order to witness the effects that it creates during movement: https://www.studiodrift.com/work#/work/shylight/. The phenomenal possibilities of art in this current age are poignantly expressed by artists like those of Studio Drift. They can create programs, circuitry, and materials that so closely mimic the minute and nearly undetectable processes of nature for the human eye and in controlled circumstances, so we may become voyeurs of some of the most awesome and wondrous effects that the natural world employs.

The contemplative nature of humans is expressed in powerful ways through visual art. Spanning spiritual and secular experiences through hand derived and highly advanced mechanical processes, meditative artworks have the capacity to transport us into a realm of thoughtful introspection. By engaging in the process of creation or slow looking, the mindful act of focusing on what an artwork can offer through the pursuit of meaning and self-exploration is a worthwhile endeavour that anyone can engage in. I hope you are titillated by the examples presented in this discussion and inspired to seek your own experiences. Though we may feel restricted in our movements at this time, we still have access to the boundless reaches of the human imagination and the infinity of the cosmos that continues to motivate our philosophical search for meaning.

Jenelle Pasiechnik

Curator of Contemporary Art